Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS)

Industrial Summary

Forestry and Logging

(NAICS 1131; 1132; 1133; 1153)

This industry comprises establishments primarily engaged in logging; timber tract operations; forest nurseries; and related support activities such as transportation, reforestation, pest control and firefighting services. Logging and support activities are the two largest segments, accounting for most of production and employment. While direct exports represent a small portion of total revenues, the forestry industry strongly relies on sales from the wood products and paper manufacturing industries which export a large share of their production, mainly to the United States. The industry employed about 37,100 workers in 2023, largely concentrated in British Columbia (37%), Quebec (26%) and Ontario (13%), with a workforce primarily composed of men (85%).

Key occupations (5-digit NOC) include:

- Logging machinery operators (83110)

- Chain saw and skidder operators (84110)

- Supervisors, logging and forestry (82010)

- Forestry technologists and technicians (22112)

- Logging and forestry labourers (85120)

- Silviculture and forestry workers (84111)

- Transport truck drivers (73300)

- Conservation and fishery officers (22113)

- Managers in natural resources production and fishing (80010)

- Heavy-duty equipment mechanics (72401)

- Forestry professionals (21111)

Projections over the 2024-2033 period

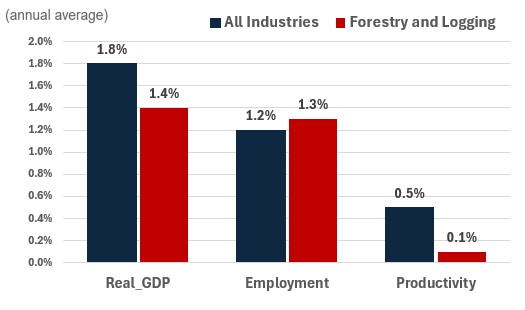

Real GDP is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 1.4%. Demand for Canada’s forestry and logging sector is largely driven by the outlook for wood, as well as pulp and paper manufacturing, and to a lesser extent, for renewable energy activities. With inflation expected to stabilise around the Bank of Canada’s 2% target, interest rates will continue to decline, supporting housing construction in the United States and Canada, thereby boosting demand for lumber in the near term. Further demand from the housing sector will come in response to higher immigration and stronger pressures on housing supply. The emergence of the biomass fuel industry and the increasing use of wood as a "greener" alternative in building construction are also expected to support demand for forestry products over the long-term horizon. On the other hand, the negative outlook projected in the pulp and paper industry will inhibit output growth in the forestry industry.

Productivity is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 0.1%. Productivity gains are expected to be very limited as growing production levels will likely require expanding activity to more remote or challenging to access locations as the reduced timber supply will change the size and location of available timber stock.

Employment is projected to grow by 1.3% annually. With muted productivity gains, employment growth is projected to be roughly in line with real GDP growth. It is expected that employers will be able to attract workers, but the exode of youth from rural communities and the growing number of lumbermen in their retirement years will continue to exert pressures on the industry’s workforce.

Challenges and Opportunities

As one of the world leading forest products producer, Canada stands to gain from the advancement of industries like biofuels and bioproducts (e.g., bio-based pharmaceuticals, compostable bioplastics, and industrial chemicals), which utilize forest biomass. This could create lucrative opportunities for the Canadian forestry industry and potential for long-term sustainable growth.

On the other hand, the sector is also under threat from climate change which can affect forest composition, rates of tree growth, and biodiversity for plant and animal species. Invasive species and insect damage could negatively impact production. Additionally, the increased risk of wildfires can cause further economic losses.

Real GDP , Employment and Productivity Growth rate (2024-2033)

Sources: ESDC 2024 COPS projections.

| Real GDP | Employment | Productivity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Industries | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.5 |

| Forestry and Logging | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.1 |