Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS)

Industrial Summary

Mining

(NAICS 2121; 2122; 2123)

This industry comprises establishments primarily engaged in mining or preparing metallic and non-metallic minerals. It is composed of three segments: coal mining (11% of total production in 2023); metal ore mining (57%); and non-metallic mineral mining and quarrying (30%). The industry exports about two-thirds of its production, mainly to the United States (26% of exports in 2023), the United Kingdom (13%), China (13%) and Japan (9%). It employed about 105,300 workers in 2023, with 46% in metal ore mining, 21% in non-metallic mineral mining and quarrying, 10% in coal mining, while the remaining 23% were not associated to any particular segment. Employment is mostly concentrated in Ontario (25%), Quebec (21%), and British Columbia (20%), and the workforce is primarily composed of men (83%).

Key occupations (5-digit NOC) include:

- Underground production and development miners (83100)

- Supervisors, mining and quarrying (82020)

- Underground mine service and support workers (84100)

- Managers in natural resources production and fishing (80010)

- Mine labourers (85110)

- Geological and mineral technologists and technicians (22101)

- Geoscientists and oceanographers (21102)

- Mining engineers (21330)

- Heavy-duty equipment mechanics (72401)

- Construction millwrights and industrial mechanics (72400)

Projections over the 2024-2033 period

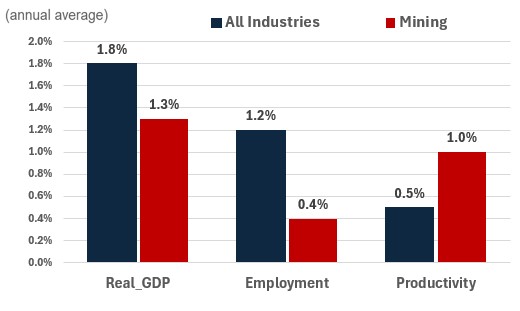

Real GDP is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 1.3%. Various federal and provincial governments initiatives will help support growth. This includes Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy, a $3.8 billion commitment to position Canada as a leader in the low carbon transition. The strategy was developed to support economic growth, competitiveness, and job creation, while promoting climate action and enhancing global security and partnerships with allies.[1] This is expected to lead to several new mines opening as Canada is looking to position itself to become a global supplier of critical minerals.

Productivity is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 1.0%, as mining companies are expected to continue and expand the deployment of automated technologies and procedures into their operations. This includes the use of radar, cameras, advanced sensing systems and other technologies powered by artificial intelligence, as well as self-driving trucks.[2]

Employment is projected to grow by 0.4% annually. Employment growth will be supported by Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy which aims at creating high quality and paying jobs. However, it will be limited by the expectation that a growing share of output gains will come in the form of productivity improvements. Canadian miners will have to prioritize productivity-enhancing measures in order to face the strong competition from several countries that have also implemented their own incentives to promote their domestic critical minerals production[3]. The mining sector might also face challenges attracting labour, including unfavorable local demographics, low post-secondary enrolment in important mining-related programs, and difficulty attracting underrepresented groups[4].

Challenges and Opportunities

One important aspect to consider, however, is that a critical determinant of Canada ability to meet its objectives is the capability to build and operate new mines. The time from exploration to production of new mines remains excessively long in Canada, which may discourage new investment. The developments of new projects, such as the Ring of Fire project in Northern Ontario, which has the potential to produce many critical minerals, still faces opposition from environmental and indigenous groups[5]. The federal government has acknowledged that this could represent a major challenge and announced measures to improved permitting processes[6].

Real GDP , Employment and Productivity Growth rate (2024-2033)

Sources: ESDC 2024 COPS projections.

| Real GDP | Employment | Productivity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Industries | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.5 |

| Mining | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.0 |

[1]Government of Canada, Introducing Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy, March 4, 2024.

[2]Amanda Stephenson, Mining companies betting on autonomous technology to make dangerous jobs safer, CBC News, June 25, 2023.

[3]International Energy Agency, Critical Minerals Policy Tracker” ,December 13, 2023.

[4]Mining Industry Human Resources Council,Canadian Mining Outlook 2024.

[5]Laura Tretheway,Inside the Fight for the Ring of Fire” , MacLean’s, September 30, 2024.

[6]Forrest Crellin and Julia Payne, “Canada to accelerate critical mineral mining – energy minister, Reuters, February 13,2024