Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS)

Industrial Summary

Health Care

(NAICS 6211-6219; 6221-6223; 6231-6239)

This industry comprises establishments primarily engaged in providing health care by diagnosis and treatment and providing residential care for medical and social reasons. It is composed of three segments: ambulatory health care services which include offices of physicians, dentists and health care practitioners, and medical and diagnostic laboratories (44% of real GDP and 33% of employment in 2021); hospitals which include general medical, surgical, psychiatric and substance abuse hospitals (40% and 47%); and nursing and residential care facilities which provide services to people with developmental handicaps, mental illness and substance abuse problems and services to the elderly and persons who are unable to fully care for themselves or who do not desire to live independently (16% and 20%). With a total of 2.0 million workers in 2021, health care was the second largest employer of the Canadian economy, behind retail trade. The workforce is primarily composed of women (79%) and characterized by a high level of education and a significant concentration of part-time workers (21%). The ambulatory health care services segment is also characterized by a strong concentration of self-employed (33%). Health care employment is distributed proportionately to population: 37% in Ontario, 22% in Quebec, 14% in British Columbia, 12% in Alberta, and 15% in the remaining provinces. Key occupations (4-digit NOC) include:

- Registered nurses and registered psychiatric nurses (3012)

- Nurse aides, orderlies and patient service associates (3413)

- Licensed practical nurses (3233)

- General practitioners and family physicians (3112)

- Social and community service workers (4212)

- Specialist physicians (3111)

- Medical administrative assistants (1243)

- Physiotherapists (3142)

- Dental assistants (3411)

- Nursing co-ordinators and supervisors (3011)

- Managers in health care (0311)

- Dental hygienists and dental therapists (3222)

- Medical laboratory technicians and pathologists’ assistants (3212)

- Psychologists (4151)

- Massage therapists (3236)

- Social workers (4152)

- Medical radiation technologists (3215)

- Other assisting occupations in support of health services (3414)

- Dentists (3113)

- Paramedical occupations (3234)

- Medical laboratory technologists (3211)

- Health policy researchers, consultants and program officers (4165)

- Other medical technologists and technicians (except dental health) (3219)

- Occupational therapists (3143)

- Respiratory therapists, clinical perfusionistsand cardiopulmonary technologists (3214)

- Dietitians and nutritionists (3132)

- Pharmacists (3131)

- Practitioners of natural healing (3232)

- Audiologists and speech-language pathologists (3141)

- Chiropractors (3122)

- Optometrists (3121)

- Other professional occupations in therapy and assessment (3144)

- Medical sonographers (3216)

- Opticians (3231)

- Cardiology technologists and electrophysiological diagnostic technologists, n.e.c. (3217)

- Instructors of persons with disabilities (4215)

- Denturists (3221)

- Health information management occupations (1252)

- Dental technologists, technicians and laboratory assistants (3223)

* Occupations in the industry also include a significant number of Light duty cleaners (6731); Food counter attendants, kitchen helpers and related support occupations (6711); and Cooks (6322).

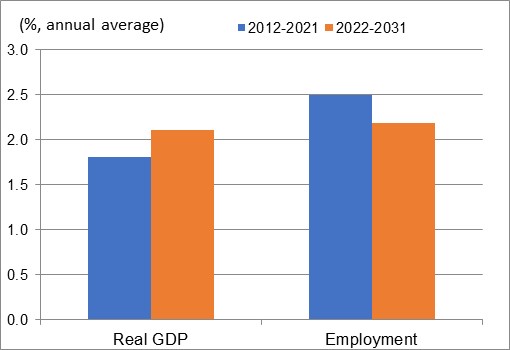

Health care is largely influenced by demographic trends in Canada and very sensitive to government expenditures in health and social programs. Demand for health care is essentially immune from cyclical fluctuations in domestic economic conditions because health care is a necessity. As a result, the industry’s output continued to increase during the recession of 2008-2009 and kept expanding at a relatively solid pace until 2019. During that period, growth in output was mainly driven by robust demand from a growing and aging population, and it would have been stronger if not for surging provincial fiscal deficits in the afterwards of the recession, which led governments to restrain public health care funding, particularly in Ontario and Quebec. Increased demand for health care, combined with expenditure constraints at the government level, resulted in long wait times for certain non-life-threatening conditions, such as knee and hip replacements, as well as lengthy delays to see specialists. The other development that took place during that period was the “delisting” of a number of services in some provinces, such as annual eye exams and physiotherapy, which became subject to restrictions or no longer covered in full by the health care system. The COVID-19 pandemic also led to major disruptions in health services across the country, with output falling by 4.2% in 2020, essentially reflecting a severe decrease in the ambulatory segment as output continued to grow in the hospital and nursing/residential segments. During that year, offices of physicians, dentists and other health care practitioners (chiropractors, physiotherapists, optometrists, audiologists, etc.) were temporarily closed or operated at reduced capacity, and many procedures were put on hold to tackle the pandemic. A large number of Canadians also delayed seeking health care for fear of possible COVID-19 exposure or concerns of overloading the system. However, the output strongly rebounded in 2021 (+8.5%) and quickly returned above its pre-pandemic level, resulting in an average growth rate of 1.8% annually in real GDP for the entire period 2012-2021.

On the employment side, increased demand for health care led to the creation of 447,000 jobs in the industry over the past decade, although growth was temporarily interrupted in 2020 (-0.3%) due to notable job losses in the ambulatory segment. The rapid spread of COVID-19 and the difficult working environment created by the pandemic also led to a significant rise in absence from work (illness, burnouts, etc.) among medical professionals. On average, health care employment increased at an annual rate of 2.5% over the period 2012-2021, largely exceeding the 0.9% recorded for the Canadian economy. In addition to strong labour demand, limited training seats for health professionals and difficult working conditions have constrained labour supply, leading to significant labour shortages in the industry. In 2021, health care services had a ratio of 0.3 unemployed worker for every vacant position, compared to an average of 1.0 for the overall economy (when excluding unemployed not classified in any specific industry). More precisely, this ratio was 0.5 for ambulatory health care, 0.4 for nursing and residential care and 0.2 for hospitals. The significant gap observed between output and employment growth over the past ten years reflected a declining trend in productivity averaging 0.7% annually. However, the concept and measurement of productivity in public health care may differ from the other sectors of the economy where goods and services are traded and more easily valued in monetary terms. Indeed, health care providers implemented several measures to improve efficiencies and lower costs over the past decade, but these changes were not reflected in the productivity numbers due to the large gains in employment. Examples of such measures include a greater focus on primary care, prevention and home care services. That said, there are still some difficulties to embrace new technologies in health care services, as evidenced by the ongoing use of paper records at the offices of some family physicians and the continued use of fax machines.

Over the projection period, output growth in the industry will continue to be driven by the recovery in the backlog of “non-essential” care treatments caused by the pandemic. A growing and aging population will also keep driving health care costs up, compelling provincial governments to increase health care funding. The commitment of many provinces to reduce wait times at emergency rooms as well as for surgical procedures and specialized treatments is expected to boost government spending and output growth in health care. The federal pledge for universal dental care is an additional factor expected to increase demand and support output and employment growth in the industry. Real GDP is projected to increase at an average pace of 2.1% annually from 2022 to 2031, a slight acceleration from the previous ten years. Employment growth, however, is projected to slow marginally, averaging 2.2% per year, but still exceeding the rate projected for the Canadian economy (+1.4%). Job creation will be constrained by labour shortages in high demand occupations (such as doctors and nurses) and fiscal challenges in provinces. Indeed, the gradual slowdown in Canada’s labour force growth is expected to put downward pressures on employment and real GDP growth across the country, which in turn will reduce growth in government revenues, thus limiting the capacity of governments to increase expenditures, including spending on health care services. In such a context, health care providers are expected to keep developing innovative approaches and implement new labour-saving ways of delivering services, leading to a better outlook for productivity. While productivity is projected to edge down by 0.1% annually on average over the period 2022-2031, most of the decline is expected to occur in 2022, reflecting adjustments to a post-pandemic environment. From 2023 to 2031, productivity growth is expected to resume but remain weak, which is nevertheless a notable improvement compared with the negative declining trend recorded over the past decade.

New models of services delivery could include the expansion of the private sector involvement in the provision of health care services, the growing use of home care for terminally ill patients, and the consideration of permitting nurses and pharmacists to perform services that used to be exclusively provided by doctors. E-health and other alternative delivery models enhanced by technology are also playing an important role in almost all processes, including patient registration, data monitoring, lab tests and self-care tools. Smartphones and tablets are gradually replacing conventional monitoring and recording systems, and people are now given the option of undergoing a consultation in the privacy of their homes. Permitting patients to access their medical files through a secure app, talking or texting with healthcare providers, and using e-consultation with some health specialists are a few of the ways to improve virtual care and potentially reduce wait times. Services are being taken out of hospital walls and integrated with user-friendly accessible devices. In addition to implementing procedures and technology to improve efficiency in the delivery of health care services, providers will continue to take steps to contain costs in the system. Such initiatives include, for example, sending patients home the same day following joint replacement surgeries. By receiving follow-up care at home, those patients are far less expensive than those staying overnight in a hospital. The increased use of midwives in some provinces and shorter hospital stays following birth are other measures that will continue to lower costs in the system. Those initiatives are crucial over the long term, given the growing pressures anticipated on public health care funding brought by demographic changes.

Real GDP and Employment Growth Rates in Health Care

Sources: Statistics Canada (historical) and ESDC 2022 COPS industrial projections.

| Real GDP | Employment | |

|---|---|---|

| 2012-2021 | 1.8 | 2.5 |

| 2022-2031 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

Sources: Statistics Canada (historical) and ESDC 2022 COPS industrial projections.